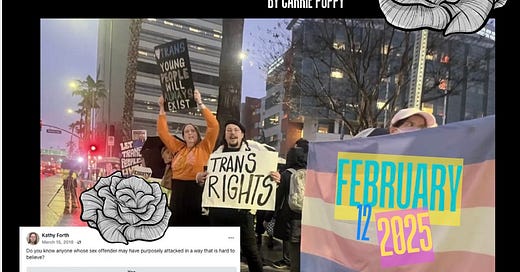

Two Suicides, a Protest, and the Media

Listening to suicide notes instead of ignoring; being brave instead of sitting by.

The other day, my friend Jesse posted devastating news.

Children’s Hospital LA (CHLA), one of the largest providers of trans kids’ healthcare in the country, was no longer initiating puberty blockers for minors.

Jesse’s family has long relied on CHLA’s services. Here’s how Jesse tells it:

I remember this time. I remember Jesse and his wife Theresa learning about their daughter’s identity, and coming to terms with the surprise of it all; it had nothing to do with outside forces (those were all working against her gender, do you hear me?); this was her own sense of self emerging.

I had seen the same thing happen in my own family, in the late 80s, before anyone had language for trans kids. My “sister” simply wasn’t a sister. I had a brother, and I can’t explain it except to tell you that I had a brother. It simply happened.

Like most parents, Jesse and Theresa were surprised and scared.

They turned to CHLA, and for a while, things improved.

But after the November presidential election, they were sweating bullets. CHLA reassured them that their children’s gender clinic would keep operating, come hell or high water.

But then January came.

When Trump signed his anti-trans executive order, the hospital almost immediately capitulated, announcing that no new minors could initiate puberty blockers through the hospital.

“Children will die. Children will die. Children will die,” Jesse wrote.

This stayed with me all day. I was driving around, thinking it: children will die.

He’s right: trans kids are at much higher risk of suicide than cis kids, and the top reasons given are so freaking changeable: (1) school belonging, (2) family support, and (3) internalized stigma. Supportive environments mitigate all three risks (no duh), but are not yet the norm. Thus, trans suicides remain common and are all but guaranteed to rise under this administration.

When reported at all, these deaths are often characterized solely as mental health events, rather than as the all-but-inevitable result of the trans person attempting to cooperate with a system that resented their participation.

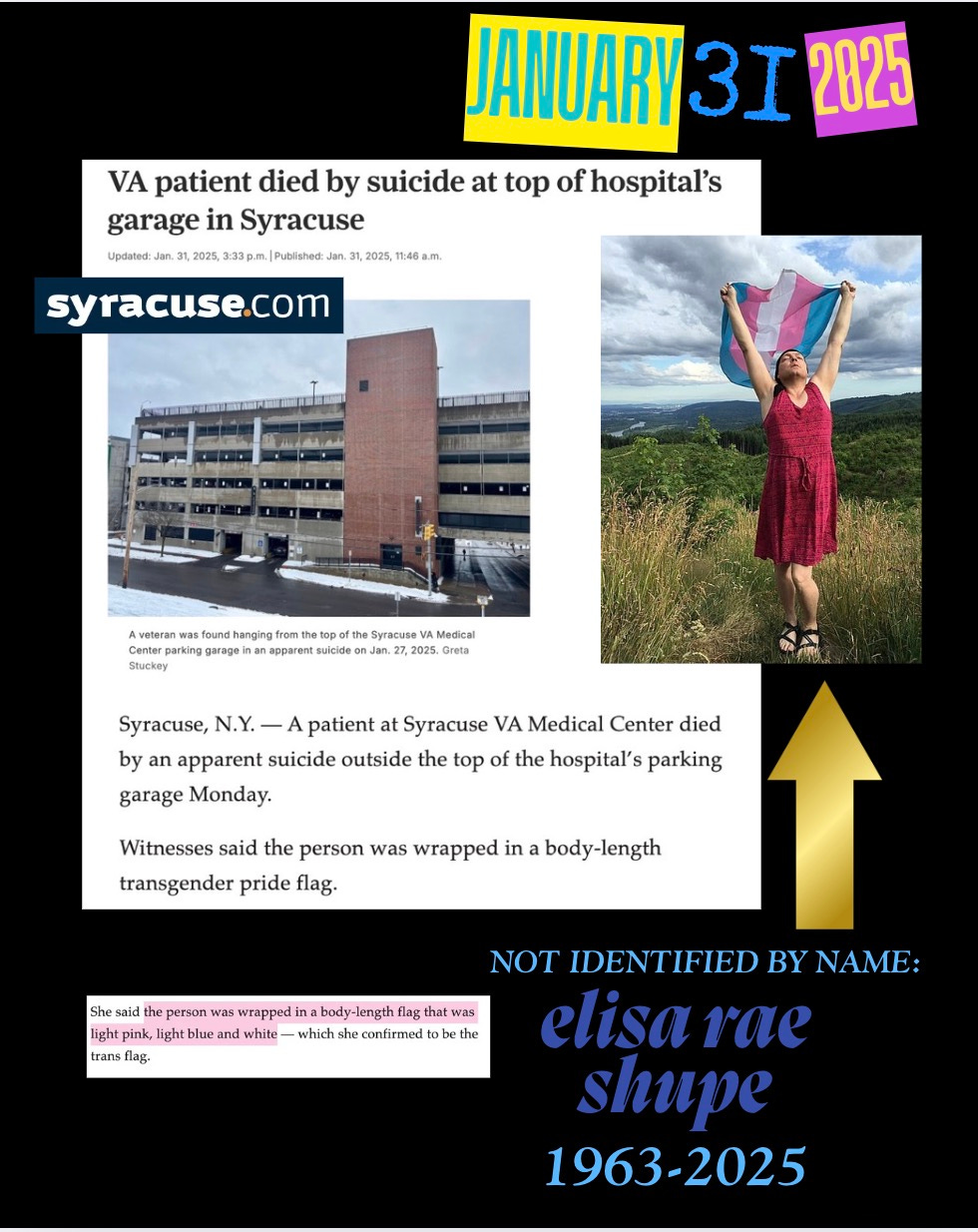

Did you know that a nonbinary veteran hanged themselves from the V.A. while wrapped in the trans flag last month?

Probably not.

I only found out about Elisa Rae Shupe’s suicide through a source, who didn’t want to go on the record.

Fortunately, someone was already on it, a Substack writer and veteran named Zero:

Four days later, Zero found what they were looking for:

Syracuse.com had posted about the suicide.

The deceadant’s name was Elisa Rae Shupe.

They were the first person to obtain the legal nonbinary “X” on the gender line of a U.S. passport, a historic achievement. At one point, they entered the controversial “detransitioner” movement, disavowing their trans identity, and racking up bylines and guest spots on conservative outlets. But this was not fulfilling, or even socially rewarding. Soon, they were aware that they had only dug a deeper hole. They returned to that X, lonelier than before, but sure of their identity.

Elisa was also a veteran, with PTSD. Recently, they had been to the V.A. for in-patient help. It was just a bit before Trump took office. When he did, he erased Elisa’s gender from U.S. law.

Now, in death, Elisa had been reduced by local media to their recent hospital stay, with their transness secondary, and their military service not mentioned at all:

But their transness was not at all secondary in real life.

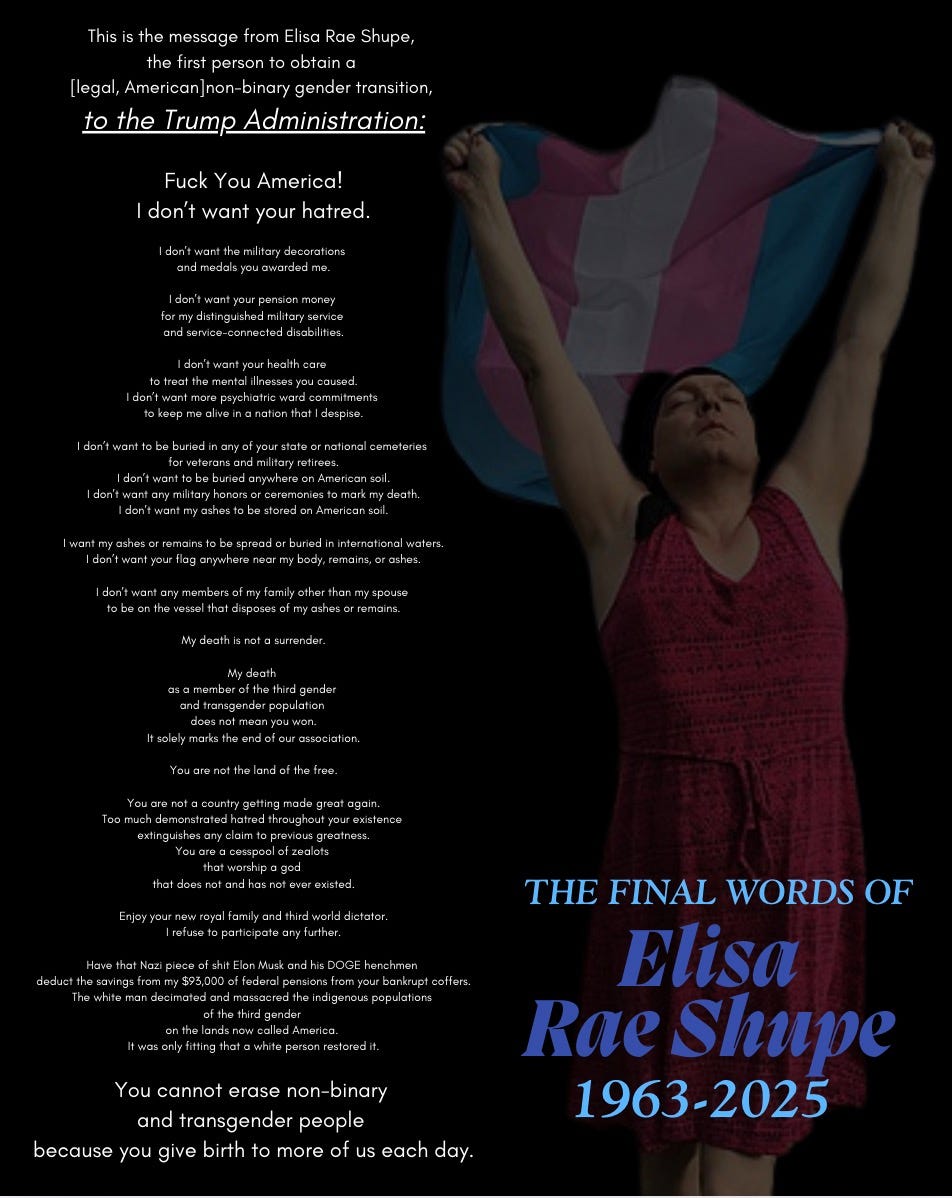

Their suicide note made that very clear.

“When I spoke about it online,” writes Zero, “I was privately messaged by someone who had confirmed the U.S Army Veteran’s name was Elisa Rae Shupe. The follower, who submitted this under the condition of anonymity, had received Elisa’s suicide note by email. My informant wasn’t the only one who had received this suicide letter. Elisa had emailed a couple of other news stations in hopes they’d publish the letter but none of them did- none of them even wrote a story.”

That shit makes my blood boil.

I really can’t stand pansy-ass news outlets that won’t report the final words of the dead, much less bother to reach out to the direct addressee of a suicide note.

In lieu of Heaven, what do the dead have except their words?

(I have emailed the White House, and will update this post if the Trump administration responds, but let’s be real; don’t hold your breath.)

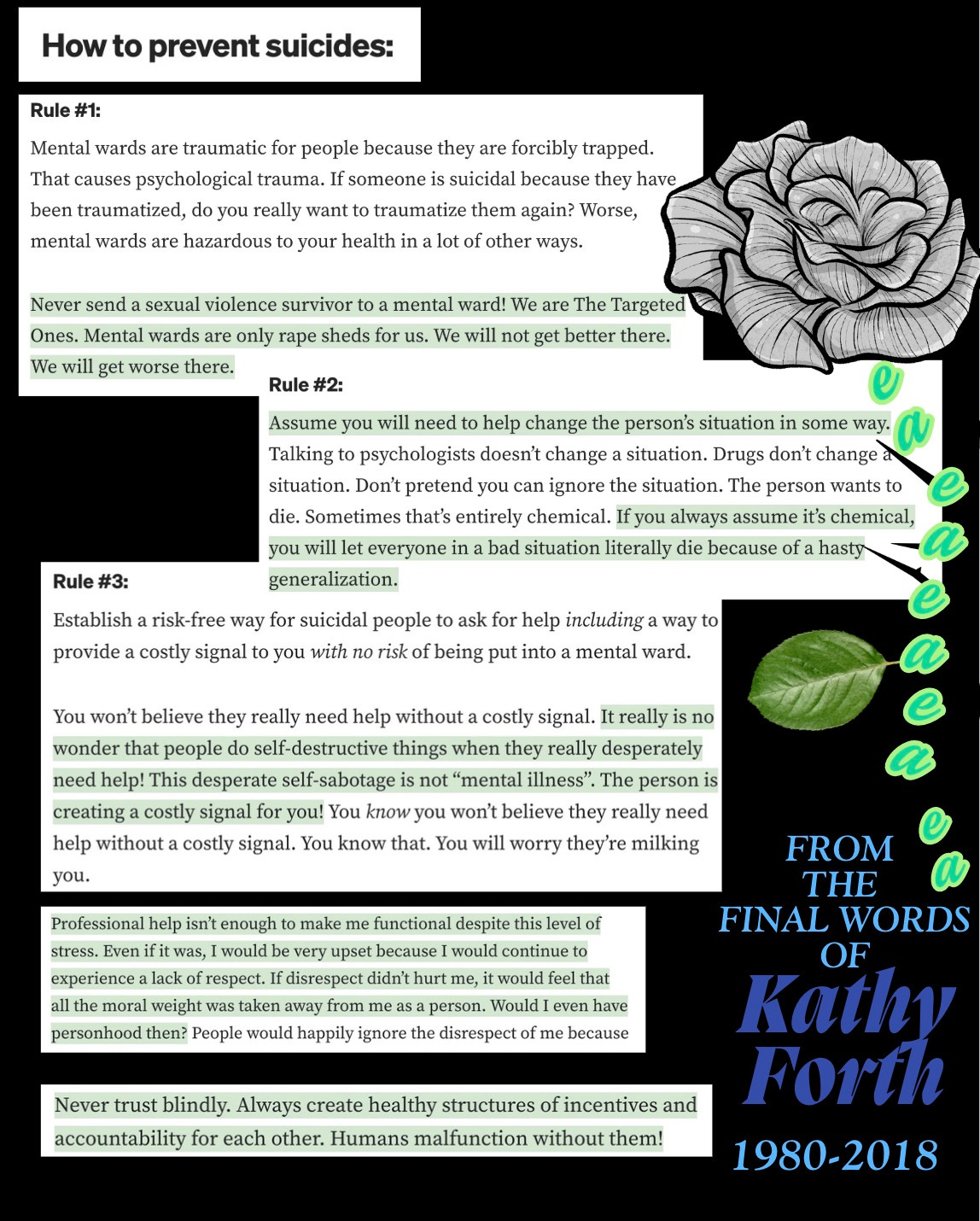

As I was reading Elisa’s note, I thought of another suicide.

Kathy Forth, a long-time member of the Effective Altruism community, deserves (and will get) her own essay.

But what I recalled, reviewing Elisa’s suicide note, was something Kathy said in her own: that people who make suicide attempts (regardless of success or intent) are sending “costly signals.” Kathy went on to give some suggestions for how to avoid suicides (like the one she was about to perform) in your own community. She spoke directly to her Effective Altruism comrades in her final letter, and begged them to be warmer to their fellows. The effective altruist community, to whom Kathy was writing, is largely wealthy and highly educated people, but notoriously stingy with time and care.

Kathy spoke to her fellows as if she believed they would change everything once they read her thorough argument for a better movement.

But she died, and almost nothing seems to have changed.

After Kathy’s suicide, her Facebook posts became part of the narrative used against her in the heavily-male EA movement. Kathy now had a “mental health history” to refer to, and that was all they needed to know.

Kathy’s “costly signal” was barely heard, as was Elisa’s.

The day after Jesse’s post about the children’s hospital, good news came:

The Attorney General of California had warned CHLA that they could be prosecuted for withholding trans healthcare from kids. Jesse posted about a protest we could go to that night to make our voices heard.

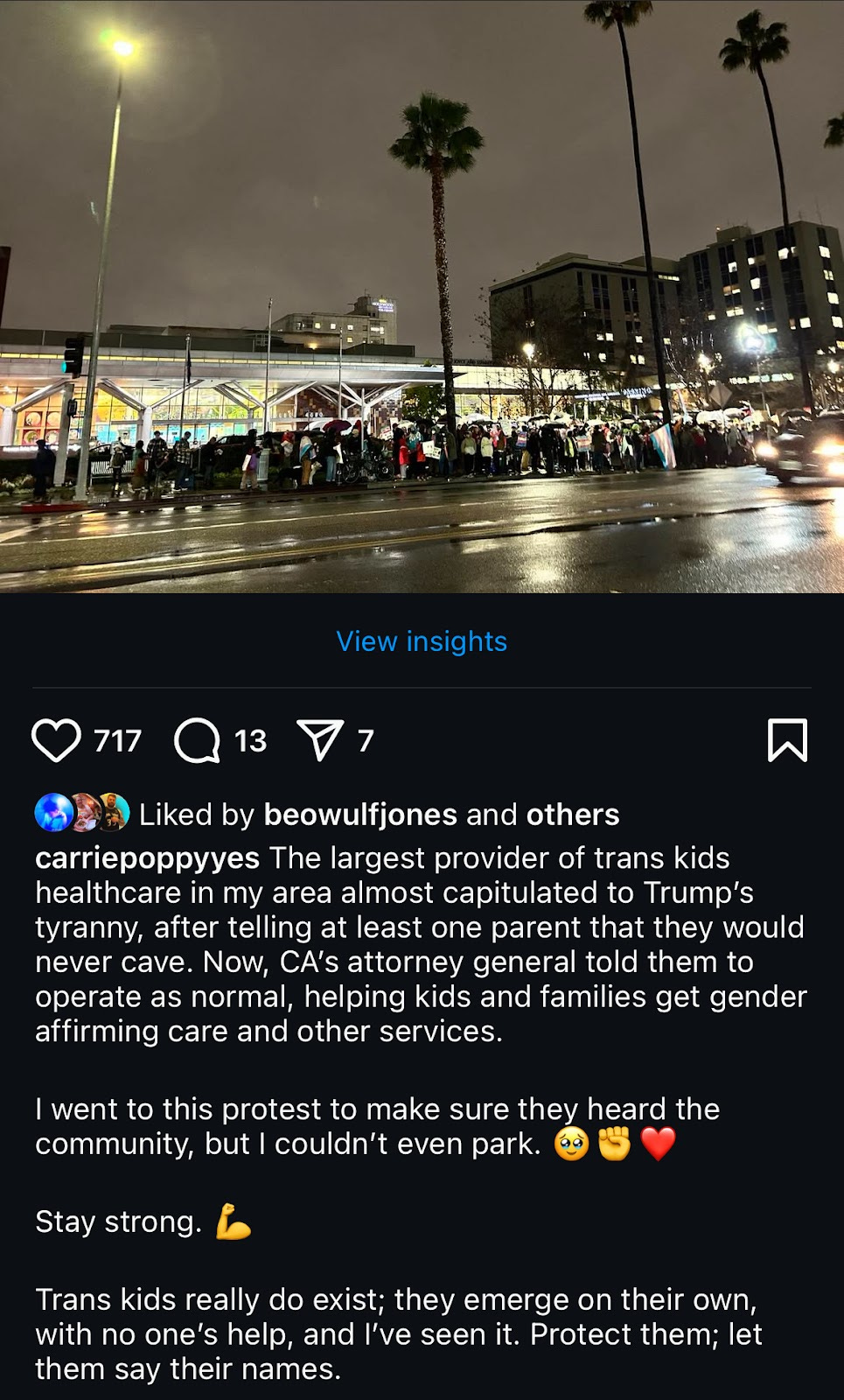

Immediately I was worried about what the turnout could possibly be on a Wednesday at 5:30 pm. Would the hospital hear from the community? Or was everyone too disillusioned to protest on a rainy day during rush hour?

Y’all, boy was I wrong to worry.

When I got there, I couldn’t even park.

It was raining, and too many of us had cared. I sat outside and grinned, from my car, at those who made it to the sidewalk. I honked and waved and took a photo. The thing was massive. I cried at the size of it. It reminded me of that scene in Milk, where the crowd comes over the hill.

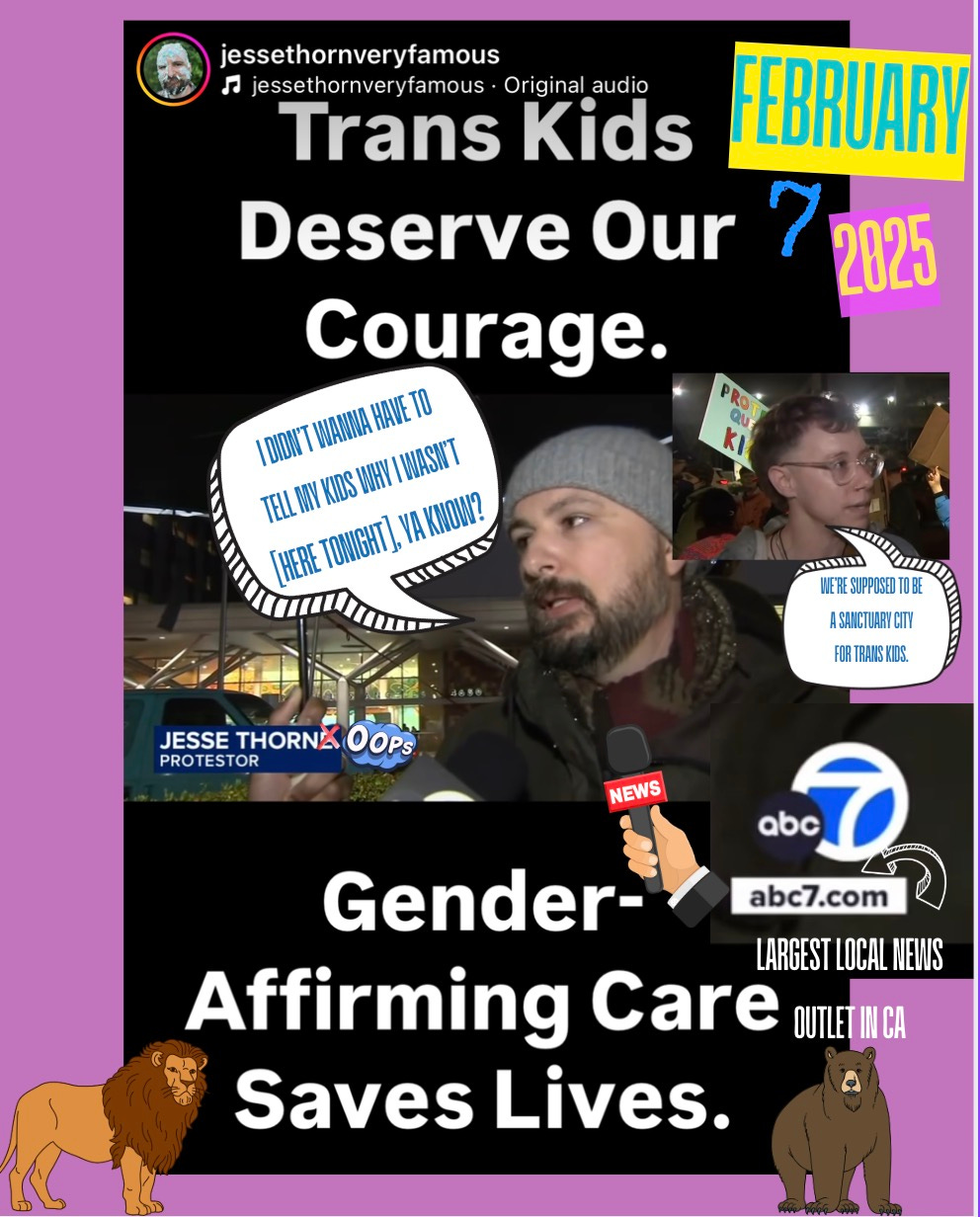

The next two days felt hopeful. There was public pressure, and the press was covering it. Our largest local outlets, the LA Times and KTLA, covered it. NPR referenced it alongside coverage of other hospitals, in other American cities, shuttering their programs after Trump’s order. At least the community and the press were not ignoring this. And my pal Jesse was right there, speaking up for his kids.

“I didn’t want to have to tell my kids why I wasn’t [here tonight],” said Jesse.

“We’re supposed to be a sanctuary city for trans kids,” said another protestor.

I am from that sanctuary city.

I grew up in La Crescenta, just over the hill.

There is damn good logic to this city having lots of trans kids, even in families and school environments that aren’t particularly welcoming.

Here’s one reason why: the arts are in L.A.’s blood, and the arts bring neurodiversity. In ridiculously brief:

L.A. is an arts hub.

Successful creative people are more likely to be neurodiverse and come from neurodiverse families.

Neurodiverse individuals are attracted to one another as friends, colleagues, and lovers, a phenomenon called assortative mating.

Arts/tech hubs are geographical autism bubbles, entrenching an increasingly neurodiverse population since Hollywood’s Golden Era at the latest. With Silicon Valley, San Francisco and Los Angeles all contributing, it’s no surprise that California leads the nation in autism diagnoses.

Autistic people and other nerodiverse individuals are more likely to be trans, intersex, or gender non conforming.

Under such circumstances, it’s hardly surprising that Los Angeles would have an unusually large neurodiverse population, resulting in an unusual number of trans kids. Ergo, to protect trans people here is to protect the unique people of Los Angeles.

As my husband Drew said, our children’s hospital “can’t be the first domino to fall.”

If it is, children will die.

Last week, I wrote about the awful phrase, “The plural of anecdote is not data.” And thirteen years ago, I gave a talk in at a U.K. Skeptics conference, called “In Defense of Anecdotes.”

But it was only sitting there, looking at that massive crowd in front of the children’s hospital, that I realized that nothing can beat what I have seen with my own eyes.

It was witnessing my brother that made the truth undeniable to me.

No one taught my (AFAB) brother to be trans.

He emerged, against hostility.

There was no contagion, no embracing arms, no coaxing. It was all the opposite.

And yet, he emerged like a tiger from its cage.

The day after the protest, I posted this:

“Trans kids really do exist; they emerge, on their own, without anyone’s help, and I’ve seen it. Protect them; let them say their names.”

That last part – that witness statement – that “I saw this, and I don’t care if you think that’s not enough” – that is the hardest part for a heady someone like me.

I want to prove it to you, instead. I want to perform the perfect argument that does it for you in just such a way that you finally see it a little bit differently, if you haven’t already.

But I cannot.

You were not there.

I can only promise my faithful account.

He emerged. The way your brother loves frogs inexplicably, and your sister was born to be a lawyer. The way your cousin was bound for the opera and your father is a boundless truth teller. It is simply how it is, and it has been evident since he was a tiny thing. I watched closer than anyone else.

I have not seen my brother in years now.

Chronically disenfranchised, he has no consistent home. When I have encountered him, I have struggled to help him. I have tried and tried, not always well. It is always my fear that disenfranchisement will kill him. But he is a rogue, and he survives against all odds, every time… so far.

I made many, many, many mistakes in trying to be a good sister to my singular and brilliant brother, but one thing I have tirelessly done is fought to know him.

The impulse to truly understand him has been in my bones since I rolled over and saw his glowing face in the bunk bed next to mine, reading books too advanced, thinking thoughts too true. My brother has a shine like no one else, and a voice all his own.

One year, for Easter,

he wrote the word SOCIETY on an egg,

and then smashed it

against a fence in our back yard.

What strikes me now,

about this memory,

is not just my brother,

with the egg in his hand.

But also his darling sister

Staring, eyes wide with wonder and awe

As her marvelous brother

Does performance art in the dirt.

She applauds for him,

an audience of one.

And makes a pact to herself

that she – I – will always tell his story.

One day, he will tell her

that his name is not what she has been calling him.

He has a new name,

and he has given it to himself.

She will not hesitate.

The sister will need no explanation at all.

That little girl – me –

who witnessed the emergence of her brother,

Will say

“Of course. It has been obvious all along!

Tell me your new name.”

That sister – me –

cannot be convinced instead

that someone stole her sister.

Some contagion or movement or outside force.

It’s just not what I saw.

My brother emerged, like a tiger, many Easters ago.

As of this writing, the Los Angeles Children’s Hospital has not budged.

Hey @Zero 🌈🏳️⚧️ i referenced your work here. Thanks for covering Elisa.

I think because we, as autistics, place so much emphasis on authenticity, we make natural allies to the trans community. Not to mention the overlap because my guess is "out" trans autistics need to express that authenticity.

These suicides are preventable. It's so maddening that "small government" is attempting to make the cure for this illegal.

Thanks for covering this. I will be sharing.